Pav Singh: How The 1984 Sikh Genocide Was Used To Win A Historic Election

"The calculation [to immediately call parliamentary elections] relied on the nation’s Hindu majority casting their votes in sympathy for his mother as a means of venting their anti-Sikh feelings..."

Pav Singh

November 2, 2022 | 9 min. read | Book Excerpt

Extract taken from 1984 India’s Guilty Secret by Pav Singh (published by Rupa, India and Kashi House, UK).

The government of the world’s largest democracy wasted no time in capitalising on the bloodletting, in the weeks following the November 1984 genocidal massacres of Sikhs. This mass crime took place throughout Northern India, following Mrs Gandhi’s assassination, where thousands were murdered by mobs organised by a section of the ruling Congress Party. Yet little is known about what happened to those who managed to survive the carnage.

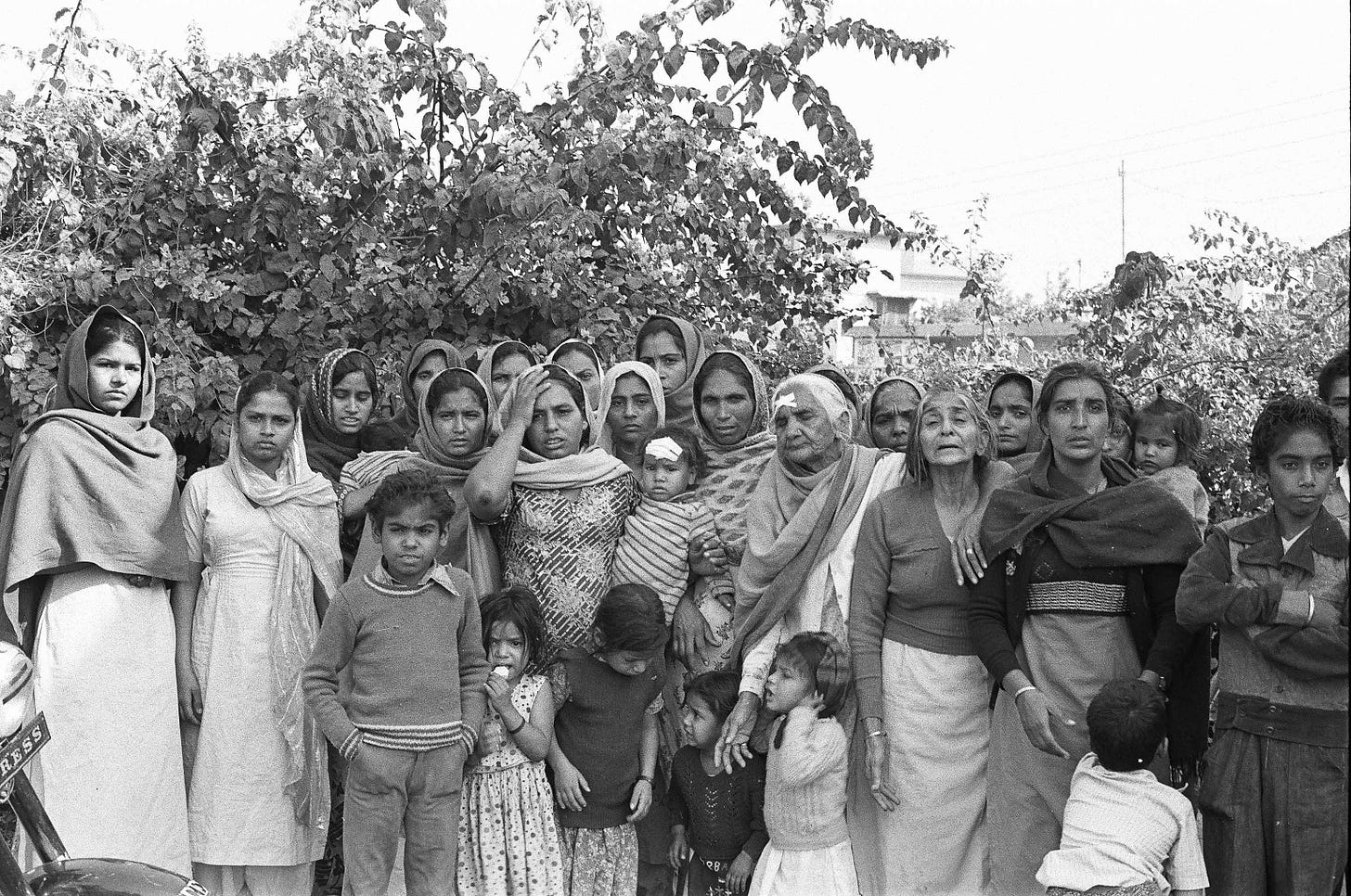

By 4 November, just four days after the outbreak of the vicious and widespread bloodletting, the violence appeared to have subsided almost as quickly as it had erupted. In its wake remained thousands of wounded and distressed, among them countless widows and orphans. Entire communities, particularly in the outer suburbs of Delhi and other towns and villages spanning the so-called Hindi cow belt, had been burnt, looted, tortured, executed, raped and essentially erased from the ground up, leaving nothing but charred human remains amongst the dying embers of their Gurdwaras and towns.

The immediate aftermath saw survivors relocate to ‘relief camps’ or simply flee. It is estimated that up to 50,000 became internally displaced. Many heads turned towards Punjab, while others who could chose to leave the country altogether. Thirty-seven years on from the monumental horrors of the division of the subcontinent in 1947, a beleaguered community was once again on the move to reach safety.

In those first few crucial days, the Congress government made little or no attempt to help the victims, who barely clung on to life. Thousands went hungry and many died of their injuries as hospitals and medical staff continued to refuse to administer much-needed treatment.

In stark contrast to this callous and pernicious negligence, interfaith voluntary organisations such as the Nagrik Ekta Manch (Citizens Unity Forum) and the gurdwaras that still remained standing stepped in to fill the vacuum. Relief in the form of food, clothing and medicine was organised for victims. They also organised peace marches despite opposition from the police.

For some of the camps’ residents, it seemed as if all hope had evaporated. Victims told and retold their terrible stories to one another. Traumatised women and children spoke of witnessing the carnage and burnings carried out by stranger and neighbour alike. One young man, a witness to his friend’s murder, described the absolute powerlessness felt by the survivors in these camps: ‘There were all these grieving people. Some had lost their families, some their businesses, and some even their sanity. It was surreal’.

The survivors knew exactly who was behind the violence. They were, after all, first-hand witnesses to the organised massacres by death squads, which had been aided and abetted by a number of politicians and police.

At the camp at Janakpuri, a residential neighbourhood in west Delhi populated predominantly by Punjabi settlers after Partition, the survivors took a stand against the perpetrators. Unwilling to be silenced by threats, they erected a signpost at the camp entrance with the declaration: ‘Sorry, no Congress politicians allowed’. It was placed next to another sign that stated: ‘No stray dogs allowed’. Both were later removed by the police.

Realising the camps were politically inconvenient – drawing attention as they did to the enormity of the crime – and anxious to proclaim the restoration of normalcy, the administration started to ‘forcibly evacuate’ those displaced and send them back to what used to be their homes, which are now ‘cinders and ashes’. It was within these shattered communities that they had watched loved ones being hacked, raped and engulfed in flames. Now they were expected to return to the burnt-out, empty shells that were once their homes, compelled to live amongst the very murderers who had looted and killed their families.

All the while, stray incidents of looting and murder continued, despite the presence of the army. In an interview recorded two decades after the massacres, the then trainee surgeon, Swaran Preet Singh, described his experience of visiting the west Delhi suburb of Hari Nagar, which became home to many of the Sikh widows. A few days after the pogroms he came across a young girl who had been raped and molested:

“She was taken to the hospital but, like so many other victims, refused treatment. A few weeks later, in another incident, an elderly woman was brought by the police. She had explained that her son was being held at a police station for a minor offence before the killings. As rumours were rife that Sikh prisoners were being killed, she decided to go herself to see if her son was safe. The station house officer shouted at her ‘yes we have killed him, now fuck off’. She started wailing and tried to hit him. They arrested her and badly beat her up. When she was brought to the hospital and complained to the doctors of her treatment, the police told them she was lying. She was in a bad way, beaten all over her body, with bruises covering her face, breasts and thighs. With further probing she admitted that they had stuck a baton into her vagina.”

Although the events of November 1984 had shaken him, Swaran Preet Singh decided to put his skills to use as a volunteer doctor. However, he was ill-prepared for what was to come:

“The widows were in a perpetual state of mourning, so absorbed in their own grief. Yet nobody was paying attention to the children… When I started working with the child victims, I saw and heard things that haunted me for years. I couldn’t sleep at night. I left Delhi, never wanting to come back.”

One of the boys in his care was so psychologically scared that he would ascend to the rooftops and threaten to jump, screaming in desperation for the man who killed his father to be found. For many of the widow’s lives became too much to bear. Some gave up their lives by plunging into the Yamuna River, while others simply became destitute.

What saved many Sikhs was the community’s ‘spirit of optimism’ or chardi-kala – positivity in the face of seemingly insurmountable odds. Those who made it through the bloodshed relatively unscathed provided succour to others who had lost everything. Volunteers serving free food, the langarwallas, not only ensured that no one went hungry, but they also provided emotional support to the widows, whom they affectionately referred to as their sisters, in an attempt to give them a sense of identity and belonging once again.

Despite accusations beginning to mount regarding the involvement of his Congress Party colleagues in the violence, Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi remained steadfast in refuting such allegation. While initially calling for calm and the reinstitution of law and order in his first radio broadcast to the nation on 31 October, within a fortnight he was announcing immediate parliamentary elections. The calculation relied on the nation’s Hindu majority casting their votes in sympathy for his mother as a means of venting their anti-Sikh feelings – feelings that had been stirred from the outset of the planning of the violence and which now would become shockingly overt in their manifestation.

An anti-Sikh backlash formed the central theme of the election campaign. The demonisation of the Sikh community that underpinned the massacres was now projected via mainstream media. Huge billboards went up around India showing posters of Sikhs brandishing automatic weapons over the bullet-ridden body of the former prime minister. Their message to voters was simple – unite against sinister forces (namely Sikh separatists in Punjab and their Pakistani backers) that threatened the integrity and security of the beloved mother land. There were even sightings of advertising hoardings showing two Sikhs in uniform gunning down a blood-stained Mrs Gandhi against the backdrop of a map of India.

The general election was slated to take place at the end of December 1984, up until which time the government offensive against Sikhs continued relentlessly in the national print media. Newspapers carried full-page advertisements employing alarming imagery of barbed wire with the splash headline: ‘Will the country’s border finally be moved to your doorstep?’ Posters of Congress candidates prominently displayed in Delhi asked: ‘Would you trust a taxi driver from another state? For better security, vote Congress.’ Given that a significant proportion of Delhi’s taxi drivers were Sikhs with their roots in Punjab, the insinuation was abundantly clear.

With the constant barrage of attacks on the Sikh community in local, state and national discourse, it was only inevitable that members of the general public would begin to openly express their hatred. In one instance, Prakash Kaur, a Punjabi teacher at Delhi University, described how children threw rotten food into her home while her work colleagues joked about the massacres; chillingly they also expressed their feelings on how Sikhs should be treated: ‘These people should be grabbed by their top knots, whirled around and beaten up thoroughly’.

Others shamelessly gloated about seeing Sikh gurdwaras consumed by flames and how they had ‘taken out the Guru Granth Sahib, spat [on] it, and urinated over it’. Prakash Kaur recounted how a fellow Sikh bus passenger was humiliated with cigarette smoke – tobacco being a prohibited substance according to Sikh tenets:

“The other day I was in a bus, which three young college students got into. One of them lit a cigarette and made sure that the smoke went right into the face of a middle-aged Sikh travelling in the bus, blowing directly on to his face. The man sat there looking quietly sullen, choking his anger in the face of such a flagrant abuse.”

Days after the killings, the stench of burning flesh still in the air, the situation was a source of amusement for some. A retired foreign office civil servant remembered his friend’s children telling him about the jokes that were doing the rounds in some of the elite Delhi schools: ‘What is a burnt Sikh? And the answer is - a seekh kebab’. In Germany after the war, many Germans would claim they knew nothing about the death camps. Disturbingly, in India, the burnings were not only common knowledge, they were celebrated.

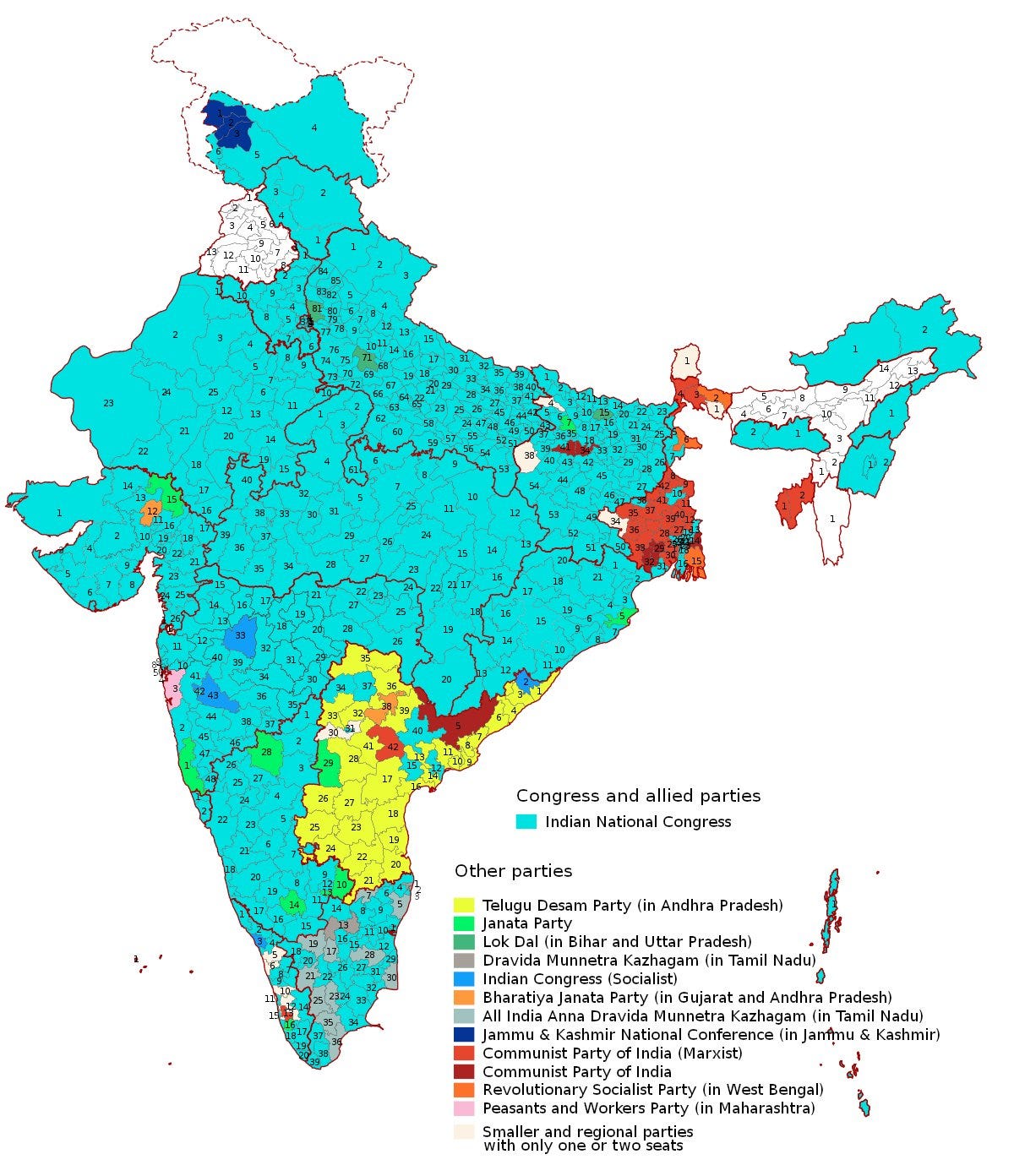

The Congress Party’s election campaign strategy proved remarkably effective. Rajiv Gandhi achieved a massive landslide in the December 1984 elections, winning 404 out of 533 seats (267 were required to achieve a majority). His mandate was unprecedented.

In his first public rally as prime minister on 19 November, Rajiv Gandhi spoke to thousands of his supporters, just a fortnight after the massacres:

“Some riots took place in the country following the murder of Indiraji. We know the people were very angry and for a few days it seemed that India had been shaken. But, when a mighty tree falls, it is only natural that the earth around it does shake a little.”

From his podium, the prime minister presented his casual justification for the mass murder of thousands of his fellow citizens explaining them away as ‘some riots’. It was a natural phenomenon, spontaneous and tragic but only to be expected, nothing of any greater consequence and stated his party men were not involved. The narrative of the ‘riot’ would set the stage of the judicial cover-up.

In a further sickening blow to the survivors and to justice, the very politicians named by victims as spearheading the violence would see huge increases in their majorities following the elections. They would also continue to build their political careers in the years that followed.

Not one of the accused was arrested. Indeed, journalists would witness several of the accused politicians at police stations busily trying to secure the release of their supporters who had been members of the killing squads.

Pav Singh was born in Leeds, England, the son of Punjabi immigrants. As a member of the Magazine and Books Industrial Council of the National Union of Journalists he has been instrumental in campaigning on the issues surrounding the 1984 massacres.

In 2004, he spent a year in India researching the full extent of the pogroms (from which members of his extended family narrowly escaped) and the subsequent cover-up. He met with survivors and witnessed the political fall-out and protests following the release of the flawed Nanavati Report into the killings. His research led to the pivotal and authoritative report 1984 Sikhs’ Kristallnacht, which was first launched in the UK Parliament in 2005 and substantially expanded in 2009.

In his role as a community advocate at the Wiener Library for the Study of the Holocaust and Genocide, London, he curated the exhibition ‘The 1984 Anti-Sikh Pogroms Remembered’ in 2014 with Delhi-based photographer Gauri Gill.

Baaz is home to opinions, ideas, and original reporting for the Sikh and Punjabi diaspora. Support us by subscribing. Find us on Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, and TikTok at @BaazNewsOrg. If you would like to submit a written piece for consideration please email us at editor@baaznews.org.