3HO's Boarding Schools Were A Living Hell

"The boarding schools were just one part of what several people born into 3HO describe as a nearly 50-year-long child-rearing experiment gone horribly wrong"

Philip Deslippe and Stacie Stukin

March 27, 2024 | 17 min. read | Original Investigative Reporting

During the monsoon season in the fall of 1981, a group of American children, some as young as five years old, traversed deep puddles full of leeches on a treacherous walk to their new school in the Himalayan foothills. They had travelled thousands of miles away from their parents; white Sikh converts and followers of Yogi Bhajan, a former customs inspector in New Delhi who arrived in the United States in 1968 and transformed himself into a yoga guru.

Norman Kreisman, then known as Baba Nam Singh, helped escort the children to Guru Nanak Fifth Centenary School in Mussoorie, India. He remembers the children crying a lot and needing help with everything.

“They were totally shell-shocked, like basket cases,” he recalls. “One of them said their parents didn’t even say goodbye.”

That year marked the beginning of a practice where children raised in Yogi Bhajan’s Healthy, Happy, Holy Organization (3HO) were sent to residential boarding schools in India.

“We were on the other side of the world from our parents, hungry and underfed, dirty, sick, supervised by bullies and alcoholics, and often left to forage for food on our own,” said S.K. Khalsa, a combat veteran in their 40s who went to India in 1991.

Baaz conducted 86 interviews with 49 people over a period of nine months, including survivors, current and former 3HO administrators and community members, lawyers, and subject matter experts. Some spoke on the condition of anonymity. The reporting uncovered the identity of two alleged pedophiles within 3HO, along with first-hand testimonies of abuse and evidence that, for decades, the organization chose to handle cases of malfeasance internally rather than contacting law enforcement.

The boarding schools were just one part of what several people born into 3HO describe as a nearly 50-year-long child-rearing experiment gone horribly wrong. In 3HO ashrams, summer camps, and Indian boarding schools, they suffered sexual, spiritual, and psychological abuse, as well as physical assault, malnourishment, medical neglect, unsanitary conditions, corporal punishment, solitary confinement, hazing, and bullying.

The abuse went unaddressed until 2020 when adult survivors came forward to tell their stories. Two years later, the Siri Singh Sahib Corporation (SSSC), which oversees 3HO, acknowledged harm caused within their schools and institutions and established the Independent Healing and Reparations Program for the Sikh Dharma Community, which ended in December 2023. Nearly 600 survivors filed claims alleging thousands of incidents of abuse.

For some, the program represented an overdue reckoning and a chance to receive financial settlements. Others described the process as retraumatizing, a way for the organization to stay out of court and avoid adequate financial and reparative accountability for decades of systemic abuse.

The SSSC declined requests for comment.

The man who later became known as Yogi Bhajan came to Los Angeles via Canada as Harbhajan Singh Puri in late 1968. He attracted counterculture Hippies seeking spiritual wisdom from the East by teaching what he claimed to be an ancient, previously secret form of yoga he called Kundalini Yoga and combining it with New Age thought and Sikhi. As his follower base grew, they established residential ashrams and yoga centers around the country and promoted his teachings.

Yogi Bhajan called himself a master of Tantra and a Saturn teacher. His mercurial and often abusive behaviour was seen by his students as a path toward spiritual growth. He legally incorporated his form of Sikhi, “Sikh Dharma,” as a religion in the state of California in 1973 and claimed the title of “Siri Singh Sahib” or leader of Sikh Dharma in the Western Hemisphere.

The following year, he established the Siri Singh Sahib Corporation (SSSC), which gave him temporal authority over the assets of Sikh Dharma, and encouraged his followers to donate money and sign over their homes, businesses, and inheritances. Through the SSSC, Yogi Bhajan soon controlled an array of non-profit entities and for-profit businesses.

Yogi Bhajan used his religious authority to give his followers a prescriptive lifestyle. He gave them spiritual names, arranged their marriages, and told them to dress in all-white clothing and how to eat and sleep.

As 3HO members began having children, Bhajan described their offspring as saints, sages, and little yogis—heroes who were blessed to be Sikhs in a community that practiced Kundalini yoga. These children, he said, were destined to lead humanity.

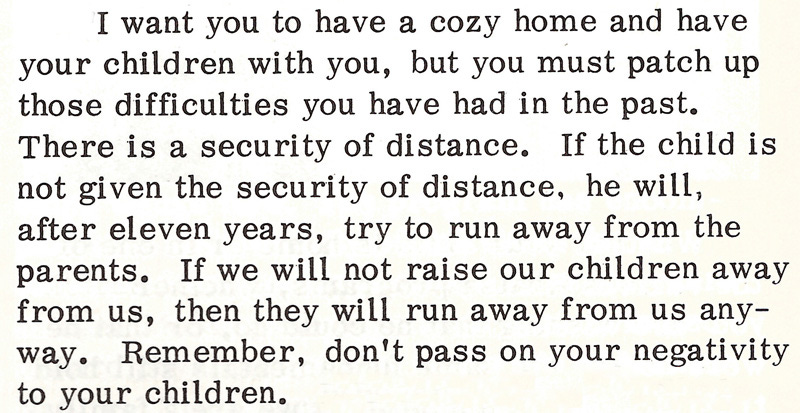

But he also told parents they were too neurotic and ill-equipped to raise their own children and risked harming them by being too affectionate and attached. The solution: separate parents from children in what he called “distance therapy.”

As early as 1974, distance therapy included separating parents from their kids by sending them to live with other 3HO families in the United States. Later, the children were sent to school in India, where Bhajan advised parents that their children would be protected from the corrupting influence of a materialistic American society full of violence, drugs, and sex.

In 1981, the first children sent to India went to Guru Nanak Fifth Centenary School in Mussoorie. From 1989-1993, they went to Guru Ram Das Academy in Dehradun, and in 1996, after several transitional years at various schools in Amritsar, 3HO opened its own Amritsar school.

Miri Piri Academy (MPA), built on land owned by the Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee (SGPC), was leased to 3HO at nearly no cost for a 99-year period. According to its website, MPA is still a boarding and day school.

Representatives from the SGPC and MPA declined to comment.

Deva Kaur Khalsa started practicing Kundalini yoga at 17, and Yogi Bhajan arranged her marriage. She sent her son Siri Amrit Singh Khalsa to live with another family when he was 17 months old. Years later, he and his sister, Guru Amar Kaur Khalsa, were sent to school in India, a decision Deva Kaur now regrets.

“The amount of trauma my kids and all the kids have endured, I now know it was typical cult behavior to separate children from their parents,” she said. “It was a warped philosophy, and he (Yogi Bhajan) used our lives like chess boards.”

For Siri Amrit, this meant years of absence from his parents. At eight years old, he was sent to Guru Ram Das Academy (GRD). He was bullied, malnourished, lacked access to clean water, and suffered medical neglect that continues to affect his mental and physical health.

“At GRD, I was starving,” he recalls. “I would drink water even though it gave me diarrhea, and I would eat rose petals. If someone had a ramen cup, kids would beat the shit out of each other for it. Food was like gold; food was everything.”

Yogi Bhajan claimed that the harsh conditions of the India school program would instill independence and grit. In 1991 Bhajan told the Khalsa Council, comprised of high-ranking 3HO members and Sikh Dharma ministers, many of whose children went to India, “I like one thing in that program [sic] it is sending our children to a living hell and making them to survive so no hell will be hell for them ever.”

After Siri Amrit graduated high school in India, like many born into 3HO, he was encouraged to work for 3HO businesses and institutions for substandard wages and discouraged from enrolling in college. Eventually, he continued his education and graduated from university with honours and a business degree. Today, he is a business consultant in British Columbia.

In 2010, at the age of 27, Siri Amrit got a job as a bookkeeper for MPA. There, he saw first-hand 3HO school administrators who had no formal education credentials or training in child development. Many were former Indian school students raised within the 3HO system who continued an existing culture of abuse by inflicting the same kind of mistreatment they experienced as children upon those in their care. During Siri Amrit’s time as an MPA employee, a student died in a drowning accident on a supervised field trip, a Chilean teacher named Satya Amrit Singh was found dead in the bathroom, and a boy was sodomized with an object by fellow students.

When he became the school’s Chief Financial Officer in 2013, Siri Amrit described frustrating attempts to get the SSSC to adequately fund the school, improve the curriculum, hire adequate numbers of qualified administrative staff, and finance infrastructure improvements.

“A lot of other religious communities have amazing schools because they believe kids are the future, and they will fund that,” Siri Amrit said. “3HO has never invested in their children on an institutional or leadership level. Our school system was just another con to steal money from the families in the community, to splinter and fracture it so more families were dedicated to Yogi Bhajan and his institutions.”

Siri Amrit’s younger sister Guru Amar, now a digital creator in her 30s, was sent to MPA in 1999 at eight years old. As an adult, she learned there were high levels of lead in the school’s water system and that a river of sewage ran through the campus. She recalls mold in the dorms, pictures of Yogi Bhajan on the walls, and education priorities that emphasized Kundalini yoga and meditation over academics.

During her first year at the school, she and others in her dorm allege they were sexually abused by Kirpal Singh Khalsa, a 3HO white convert, who is named as the school’s Academic Director on Guru Amar’s report cards. He and his wife, who was a designated caretaker, lived across the hall.

Kirpal Singh declined to comment.

“We were nine years old when he started molesting and grooming us,” Guru Amar said. “I was too young to know something was wrong, but one of the other girls was extremely aware, and she started wearing a swimsuit under her clothing.”

In 2002, when one of Guru Amar’s classmates told a 3HO staff member in India about the sexual abuse committed against her and others, Kirpal Singh was sent home to the United States, and Guru Amar said they were told not to talk about the abuse.

Over the course of 16 years, Deva Kaur and other mothers tried to make the organization address the abuse of their children. They wrote letters to and met with 3HO officials expressing concern for their daughters and the safety of other girls in the community but were discouraged from talking publicly about the abuse.

“The situation was handled pathetically,” Deva Kaur said. “We sacrificed our children’s childhood and trusted a spiritual school, and to have our kids sexually abused was just enraging. I feel the guilt for having agreed to it.”

The SSSC Office of Ethics & Professional Standards (EPS) did not officially acknowledge the harm until 2018, when Guru Amar and some of her classmates filed a formal complaint.

It took until May of 2023 for the EPS to publicly state on their website that Kirpal Singh committed “misconduct with minors.”

Over the decades, Kirpal Singh was one of at least five alleged pedophiles in 3HO who preyed upon children inside and outside the 3HO community.

Additionally, Baaz confirmed the reparation program settled no less than three claims for harm caused by a man named Narayan Singh Khalsa, who joined the Los Angeles 3HO community as a white convert in the early 1980s.

According to survivors and their families, he allegedly abused boys over the course of several decades as a volunteer guide at 3HO summer camps, as a caretaker during the Winter Interim program in India, and at his house in Phoenix across from the 3HO Gurdwara where he had a playground in the yard and video games inside.

Karta Singh, now in his 40s, grew up in Phoenix, Arizona and was sexually abused by Narayan when he was nine years old. Karta alleges that while he was sleeping at Narayan’s house, he made him watch pornography and then assaulted him. “I really didn’t know anything about sex,” Karta said. “I felt very ashamed afterwards. I hid it because I didn’t want anyone to find out.”

For Karta, the trauma of those formative years led to depression, drug addiction, and being homeless for nearly a year. “Using drugs felt like a warm safe blanket,” he said. “It was a protection I never felt before.” He is 13 years sober.

Karta accepted a settlement from the reparations program. “Money can be great, but it is not going to heal anything,” he said. “Something that would help would be getting abusers off the street and making sure that they can never do this again.”

Interviews with parents, survivors, and other members of the Phoenix 3HO community revealed that numerous adults and authority figures within the organization knew about Narayan’s predatory behaviour, yet he continued to live in the same house within the 3HO community for decades.

Narayan Singh declined to comment.

Handling the abuse of children internally within 3HO was a pattern. Children were sent to 3HO therapists, incidents were handled by ashram heads or senior Sikh Dharma ministers, and abusers were counselled by Sikh Dharma therapists and Yogi Bhajan himself.

“There was always a bigger emphasis on covering up problems rather than solving them,” said Ajai Singh Khalsa, a lawyer who became CEO of Sikh Dharma International for several years after Yogi Bhajan’s death in 2004. He described 3HO as having a pervasive, unspoken culture of not going to outside authorities. “The real sin was taking problems to the world.”

Details of abuse suffered by 3HO children and the school’s poor conditions have been online for decades on forums and message boards run by ex-3HO members. Narangkar Glover, an artist in the Pacific Northwest, has been blogging about her experiences growing up in 3HO for over 15 years and today maintains the site Rishiknots.

In early 2020, 3HO was publicly forced to face its history of abuse when a former high-ranking 3HO official named Pamala Dyson self-published a memoir entitled Premka: White Bird in a Golden Cage that revealed her illicit, abusive affair with Yogi Bhajan, who was married and claimed to be celibate.

The book did not document harm done to other women or to the children raised in 3HO, but the timing of its release at the beginning of the pandemic, when everyone was homebound and connected via Zoom, allowed others to tell their stories publicly.

During an April 2020 Zoom meeting for the Khalsa Council, men and women shared testimonies about the abuse they experienced in the community while their parents and peers listened. An agenda item slated for 45 minutes turned into a 12-hour call. This was one of several Zoom calls that took place that year. For many second-generation adults, this also began a series of private, difficult conversations with family, community members, and peers.

“Growing up, we had no voice at all,” Guru Amar said. “In 2020, we were finally given the space to share the awful things that had happened to us and realize they were truly awful. We no longer had to be quiet and pretend it didn’t happen.”

For older 3HO second-generation adults like Sat Kartar Kaur Khalsa, who went to GNFC at seven and is now raising her own children, speaking out became imperative. “We were watching our own kids at the same age that we were when we were sent to India. When it comes to your own kids, you can’t lie to yourself. We knew how harmful it was (for us),” she said.

Around the same time, other second-generation women who were groomed from an early age to become part of Yogi Bhajan’s staff, many of whom had sexual, and sometimes nonconsensual, relationships with him, also came forward with their stories.

Subsequently, the SSSC commissioned a third party, independent investigation by a Buddhist organization called An Olive Branch. Their report concluded “more likely than not,” Yogi Bhajan used his spiritual authority to perpetrate a range of abuses against women, including rape, sexual battery, sexual abuse, and sexual harassment.

As the community struggled to move forward with the report's revelations and rectify the harms experienced by the second generation, the SSSC announced a reparations program in April 2022.

In recent years, reparations programs have emerged to settle claims of abuse between survivors and organizations in lieu of a trial or a lawsuit. Notable examples include the Boy Scouts of America and USA Gymnastics.

Carol Merchasin, an attorney at the British-American law firm McAllister Olivarius who specializes in defending survivors of abuse within religious communities, said, “A reparations program can help a larger group of survivors than the justice system can because the legal system doesn’t always give us a path to accountability.”

For survivors, a reparation program can provide recourse where there may not be a way to pursue accountability under the law and without lengthy and retraumatizing civil or class action lawsuits.

For organizations like 3HO, a reparations program allows for multiple claims to be settled for less than victims would be awarded in lawsuits. The claims are also settled without the organization being compelled by a court to produce evidence or have members testify under oath. Once survivors sign an agreement, they can never file a future lawsuit.

Kim Dougherty, a lawyer with the firm Justice Law Collaborative who represented over 150 claimants who grew up in 3HO, said the SSSC and their lawyers from the firm Lewis Roca represented that the program would be trauma-informed and no limits would be placed on the monetary settlements. Additionally, she was assured by the IHRP that claimants’ requests for non-monetary reparations, such as institutional reform to prevent future harm, would be prioritized.

When the SSSC raised funds for reparations, the board had progressive members who believed survivors and wanted to make amends. According to several sources with direct knowledge of the allocation, approximately $40 million was set aside from 3HO businesses to fund a program that anticipated about 100 claims. When nearly 600 people filed claims, more funding was necessary to compensate claimants, yet board members described by many as hard-liners who revere Yogi Bhajan, denied increased funding.

Even though claimants widely understood that the independent administrators tasked with assessing their awards would have no monetary restrictions, settlements were limited by that fixed $40 million pool of funds, resulting in reparations that ranged from several tens of thousands of dollars to slightly less than several hundred thousand dollars. For many, this was less than one-tenth of what they expected.

Dougherty said the program was misrepresented and woefully underfunded. “The program was a bait and switch,” Dougherty said. “The most egregious part is that the highest amount of payment is not enough money to provide a true reparation for past harm and future healing, and that’s the reason people participated.”

The reparation program was also designed to institute non-monetary requests, such as ongoing therapeutic support, a restorative justice program, public acknowledgements of harm, apologies from the SSSC and its affiliates, and institutional changes and safeguards at Miri Piri Academy and other 3HO facilities.

Several sources with direct knowledge said that discussions of safeguarding were negligible during the reparations process and to date few, if any, of these non-monetary requests have been honored.

“What matters to survivors more than monetary reparations is real meaningful institutional change—and that has not happened,” Dougherty said.

Numerous claimants also describe the program as retraumatizing and insensitive. The application asked claimants to “please further describe the nature of your harms,” which prompted many to write long testimonies, some as long as 70 pages, in hopes of making a strong case for monetary and non-monetary reparations.

Lewis Roca, the law firm hired by the SSSC to administer the program, denied requests for comment. Meena Allen, a Santa Fe, New Mexico-based attorney and the SSSC program compliance advisor hired by Lewis Roca declined to answer questions but said, “The program is pleased that it has reached a lot of people to provide compensation.”

While a large number of claimants did accept their reparation, in December of 2023, four women who were on Yogi Bhajan’s staff, three of whom were born into 3HO, rejected reparation settlements. Instead, they filed a California lawsuit against the SSSC and their affiliated business for damages alleging negligence, sexual harassment, emotional distress, and sexual battery.

One plaintiff, Kathleen Hayes, said, “The reparations program was about mitigating potential liabilities for those choosing to cover up the years of corruption.”

The lawsuit reads in part: “This complaint seeks recourse on behalf of four Plaintiffs whose lives have been permanently scarred by Yogi Bhajan’s sadistic sexual abuse and the failure of the entities herein to prevent, investigate, and respond to the sexual abuse. Yogi Bhajan’s tendencies were widely known and persisted for decades, but nobody protected the women in his midst. Plaintiffs seek recourse from the specific entities that failed to protect them during Yogi Bhajan’s reign of abuse…”

Daniel L. Varon, of the California-based Zalkin law firm representing the plaintiffs, said the lawsuit enables survivors to pursue all remedies under the law in a public forum. “Reparation programs are not designed to give survivors of sexual assault a voice, so filing a public lawsuit is a way for people to reclaim their voices,” Varon said.

As the reparation program was winding down, conservative members of 3HO, who still support Yogi Bhajan and deny claims of abuse, took control of the SSSC board. Changes that began in 2020, such as removing Yogi Bhajan’s name and image in yoga studios and on websites, were reversed.

Sahaj Singh Khalsa, a former SSSC board member who was born into 3HO and attended boarding school in India, resigned after fellow board members harassed his wife and children, and one community member told his daughter at Gurdwara: “Get your Dad in line.”

Sahaj helped to facilitate the Zoom calls and worked with the board to develop the reparations program and honour the non-monetary requests. However, his efforts were thwarted when conservative members took control of the SSSC board.

“I have been attacked, threatened, and abused for telling the truth and advocating for change,” he wrote in his resignation letter. “...In the past three years, we have denied, minimized, rationalized, and justified abuse of children.”

Sahaj said of the current SSSC board, “These are people who should not be in any position of authority or have respect. They defend pedophiles and refuse to see the experiences of people who have been harmed. This does not align with my understanding of what it means to be a Sikh. The teachings of the Gurus are to not ignore or dismiss people who ask for help. Inaction is going to harm people who have already been harmed.”

Siri Amrit, who accepted a monetary claim, said that the reparations program fell short of its claimed goals.

“If the intent was to acknowledge the abuse and create healing, it ended up as a partial acknowledgement, a partial healing, and it turned into another form of abuse. We lost dozens of kids to suicide, addiction, prison, or depression.”

“There’s a saying here in Canada with the First Nations residential schools,” he added. ‘First truth, then reconciliation.’”

Stacie Stukin is a Los Angeles-based arts and culture journalist. You can find her on Twitter at @staciestukin

Philip Deslippe is a Ph.D. Candidate in the Department of Religious Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara. You can find him on Twitter at @PhilipDeslippe

Baaz is home to opinions, ideas, and original reporting for the Sikh and Punjabi diaspora. Support us by subscribing. Find us on Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, and TikTok at @BaazNewsOrg. If you would like to submit a written piece for consideration please email us at editor@baaznews.org.

😲