Jatinder Singh: Canadian Museums Exhibiting Sikh History Must Do Better

"Care needs to be taken in ensuring exhibits are presented respectfully, accurately, and with the use of subject matter experts."

Jatinder Singh

August 17, 2022 | 7 min. read | Opinion

Over the last few years, Canadian Museums have faced an eruption of allegations related to racism and harassment. The result has been a scramble to decolonize exhibits, replace CEOs, and conduct novel approaches in how artifacts are displayed. A wholesale change in how both indigenous peoples and historically excluded groups are presented has begun.

In this push to change, religious groups, such as the Sikhs, will find that their history will also be the focus of attention. Care needs to be taken in ensuring exhibits are presented respectfully, accurately and with the use of subject matter experts. Museums must be transparent in the provenance of artifacts, i.e. where they originally came from, and make a significant effort to identify stolen ones.

Most artifacts related to Sikh history are at Gurdwaras and museums across India and Pakistan. Some artifacts have made it into the hands of private collectors and museums outside this region. The authenticity and provenance of these are often difficult to know.

Ironically, those that were taken by the East India Company after the Second-Anglo Sikh war, and presently sitting in museums, estate homes or with descendants, have the strongest provenance, as they can be linked directly back to the Sikhs. Other objects with a strong provenance include those gifted by the Royal Households of Panjab. During auctions competition for acquiring such artifacts is often intense. Thankfully, many are now coming back into Sikh hands.

In Canada, the latest exhibit on the Sikhs is a permanent display just launched at the Montreal Museum for the Fine Arts (MMFA).

Such exhibits garner much attention from Canadian Sikhs, as it is a rare opportunity to see such artifacts outside of Asia. Even though these objects receive world-class storage, handling, preservation and conservation, oftentimes they do not make it into museum spaces, and in many cases stay hidden away in storage.

The MMFA Sikh exhibit was established after years of work by the Sikh Foundation and the Chadha family from Montreal. During my visit in early July, I viewed eighteen distinct items showcased, including historic and contemporary paintings, weapons, Sikh coins, newspapers, and pictures.

Shown in Les Arts Du Tout-Monde/The Arts of One World wing, in an approximately 13 by 40-foot space, I was greeted with a large textual display mentioning the donors and financers of the collection, as well as a brief history of the Sikhs.

Artwork is displayed mostly on the walls, with two display cases showcasing more art and artifacts. At the end of the space, I viewed a wall-mounted phulkari from the 1900s. The presentation of the artifacts is to a high standard, with a description provided for each.

It was heartening to see the Museum has also purchased art from contemporary artists, such as Keerat Kaur and Jatinder Singh Durhailay. The museum is to be commended for its display and its commitment to Sikh art and artifacts.

Despite this great effort, there were some avoidable missteps that need to be considered. This is especially so as more museums consider giving space to the history and heritage of the Sikhs.

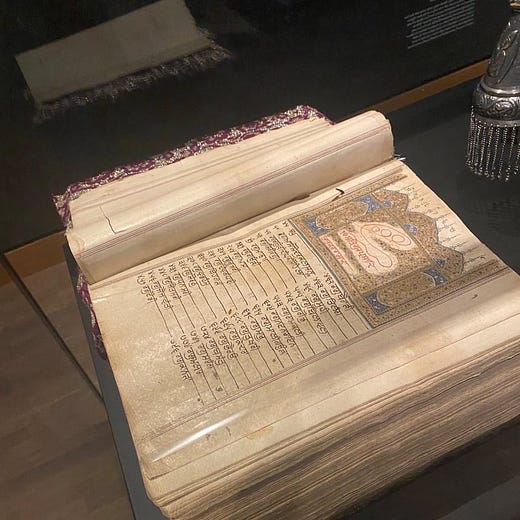

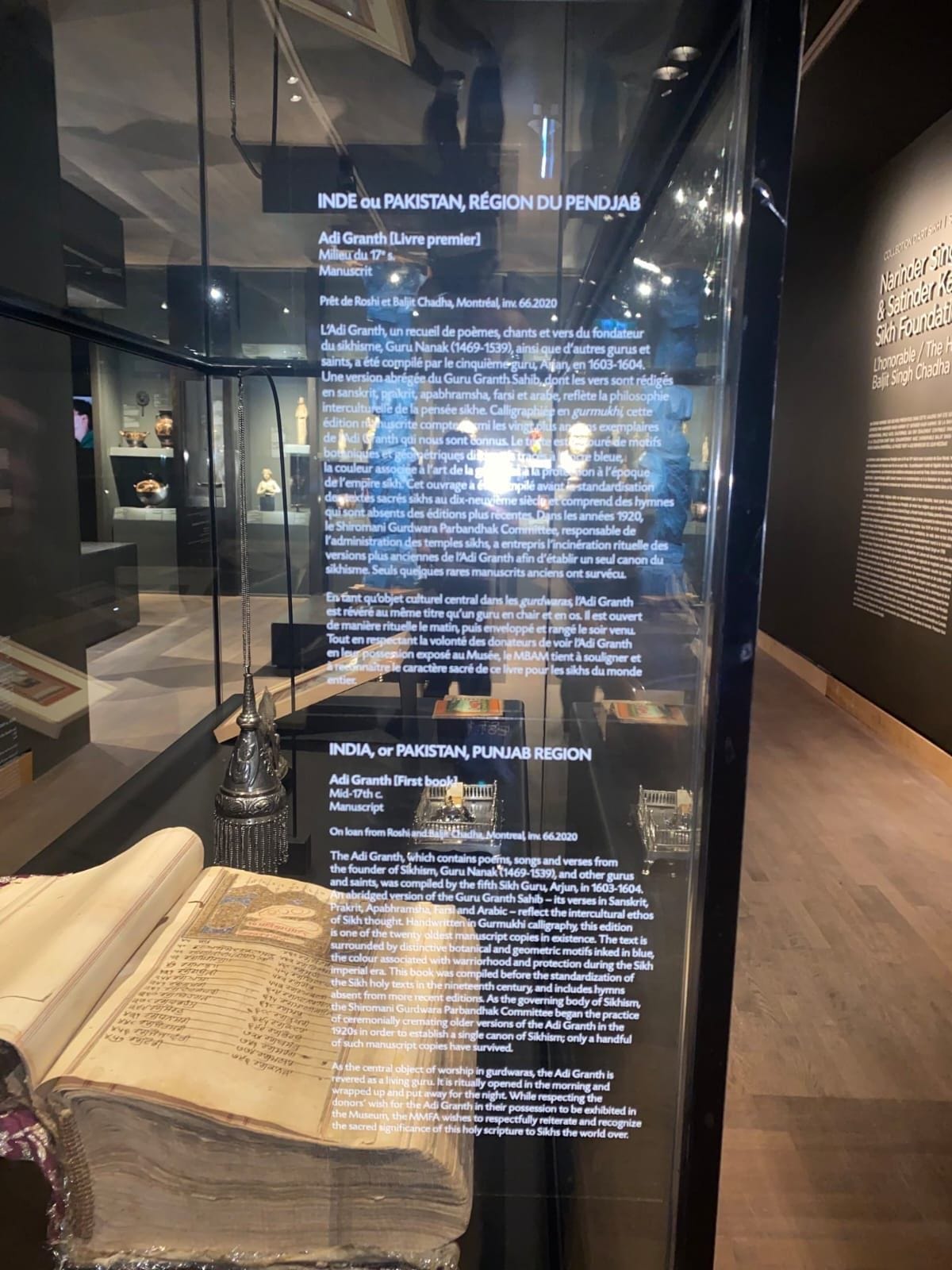

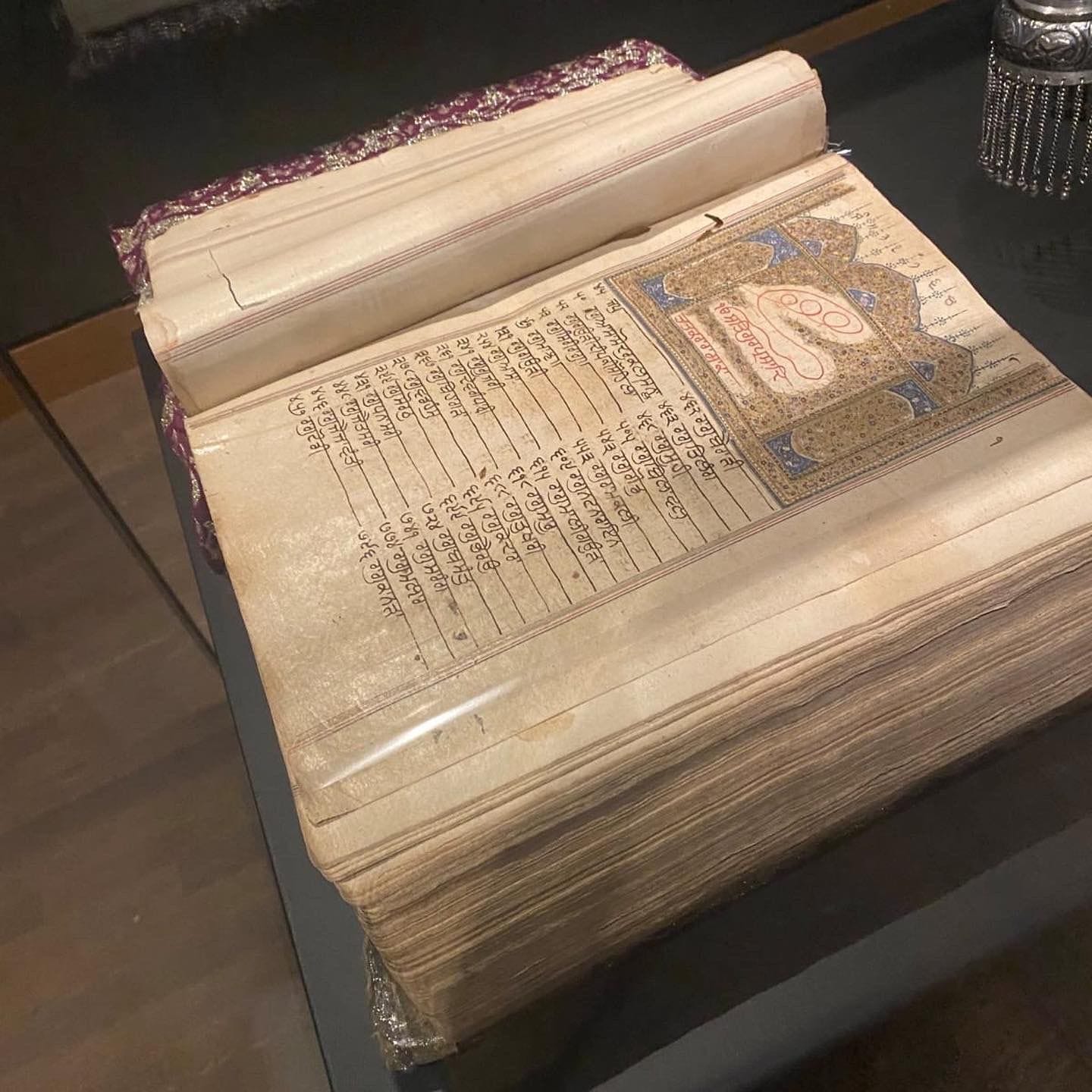

Initially, two Saroops, i.e. physical forms, of the Guru Granth Sahib were displayed.

One was from the 17th Century and the other was a miniature from World War I. While it is not unusual to show Saroops, especially those linked to specific historical events, such as the original Guru Granth Sahib or the one struck by bullets during Operation Bluestar, they are always done as per Maryada, i.e. according to the Sikh Code of Conduct.

This Maryada seems not to have been followed in Montreal, with the Saroops merely encased in a display case.

It is evident the curators were aware of this, as the associated description stated while “respecting the donors’ wish for the Adi Granth in their possession to be exhibited in the Museum, the MMFA wishes to respectfully reiterate and recognize the sacred significance of the holy scripture to the Sikhs the world over.”

Immediately after the launch, controversy ensued when local Sikhs visited the museum and deep concerns were raised.

A letter from The World Sikh Organization (WSO) resulted in the removal of the Saroops by the donor.

In my own correspondence with the museum on this matter, they declined to answer additional questions and stated they had ‘no further comments on this topic’. Such a response does not indicate the museum’s interest in promoting further dialogue to grow, but rather, an ongoing need to maintain gatekeeping and barriers to access with the very communities they should want to engage with.

WSO had also presented questions to the donor, the Honourable Baljit Singh Chadha, but has yet to receive a response.

The authenticity of artifacts is also needed.

One academic mentioned that the orthography of the Saroop, as viewed from pictures taken before its removal, did not match with late 17th Century Gurmukhi, but added that the placement of Rag Jaijaiwanti suggests its origin was certainly in the post Guru Tegh Bahadur period.

Such a Saroop requires expert study, with research that could shed so much more light on it. A digital presentation could have allayed religious concerns and with more detailed information garnered from an expert, provided the audience with a richer and more rewarding experience of the Saroop.

As of the 2001 census, Quebec has over 8000 Sikhs. Most live in and around Montreal, which also has at least eight Gurdwaras, the largest being Gurdwara Guru Nanak Darbar, LaSalle. When I queried two of these Gurdwaras, including LaSalle, both confirmed they had been completely unaware of the exhibit, whose existence only came to light after concerns were raised from Sangat about the display of the Saroops.

The Museum did not answer queries about whether they had engaged with the Gurdwaras, despite having an Art and Togetherness Committee, whose mandate is to reach out to communities.

In fact, the launch itself had the air of elitism with several of Canada’s Sikhs politicians and India’s High Commissioner attending. Many of them posted on social media about the exhibit, including showing the items on display. Surprisingly, none showed a direct picture of the 17th Century Saroop in their social media posts.

When presenting history related to the Sikhs, subject matter experts must be engaged.

For example, when describing the earliest period of the faith, it was stated that the ‘first nine Sikh religious leaders did not ask their followers, who mostly came from the merchant and farming communities of Punjab, to dissociate themselves from their original religion, whether Hinduism or Islam. It was only in 1699 that the tenth Guru, Guru Gobind Singh, created the Khalsa, the first community of Sikhs fully committed to the Guru.’

If you are devoting just a few lines to the earliest period of the faith, focusing on a false dichotomy between the first nine and the tenth Guru is disconcerting. The contested nature of the lineage of the Gurus during these earliest times was a constant thorn for them to contend with. To say, in this day and age, that Guru Nanak and Guru Gobind Singh somehow deviated in their expectation of followers, is uninformed. In describing the earliest part of the faith, not mentioning the revelatory nature of Gurbani, the institutions built by the Gurus and key historical moments are glaring.

Further, the description related to the now removed 17th Century Saroop stated it was ‘one of the twenty oldest manuscript copies in existence’. I have enquired with Sikh artifact experts, collectors and academics, and they are entirely unaware of where this number came from.

The only reference I have is of 20 Saroops with signatures of the Gurus being digitized in India. However, those were the ones the digitizers could obtain and certainly not the entirety of such Saroops.

Finally, In their description titled ‘From Sparrows to Hawks’ they describe how when the conquered Sikhs handed over power to the East India Company, their great swaths of land were ‘used by the British to transform the Punjab into the breadbasket of India’. This is an overly simplistic view that promotes British rule and ignores the damage done by agrarian colonialism in Panjab.

Transparency is needed on who curated the exhibit. Unfortunately, the museum did not reveal who this was.

The provenance of Sikh artifacts is also critically important. Where, for example, did the 17th Century Saroop come from? The removal of artifacts from India, without Central Government approval, has been forbidden since 1972.

While India is now working to get many stolen artifacts back, through initiatives like the India Pride Project, their focus has been primarily on stolen idols of deities.

It is important for Sikh institutions to know what Sikh artifacts are in the West and their provenance.

In the UK, the British Museum also has a 17th Century Saroop, which was purchased from Reverend A Fischer in 1884. How did he acquire it?

Also, most Sikhs know that the Kohinoor and the throne of Maharaja Ranjit Singh were taken from the Lahore treasury. Yet, there is so much more that was looted during the colonialism of Panjab that many are unaware of. Extensive research is needed on what was looted, what was taken after the signing of the treaty of Lahore, what was gifted, where these objects are now, and have mechanisms to create permanent spaces in Museums, in conjunction with experts, to showcase them.

We, as a community, will increasingly be the subject of exhibits, especially here in Canada. As such, we need to focus not only on what is being exhibited but also on the narrative being promoted, especially as more money comes into presenting Sikh history, both from within the community and from outsiders.

Those who are fortunate to be able to finance such exhibits should not be the final say in what and how artifacts are presented.

Community engagement is a must. Subject matter expert engagement is a must. Determining authenticity and provenance is a must. World-class storage, handling, preservation and conservation are a must. Making items accessible in Museum spaces is a must. Consider all of these musts, collaborate extensively, and we will have exhibits all will enjoy.

Jatinder Singh is the National Director for Khalsa Aid Canada. He was part of the team that presented Lapata. And the Left Behind as well as The Sikhs: Faith, History and People (Royal B.C. Museum). He has also been collecting Sikh artifacts for over 20 years.

Baaz is home to opinions, ideas, and original reporting for the Sikh and Punjabi diaspora. Support us by subscribing. Find us on Twitter, Instagram, Facebook at @BaazNewsOrg. If you would like to submit a written piece for consideration please email us at editor@baaznews.org.